Five Years Ago, I Lost My Breasts

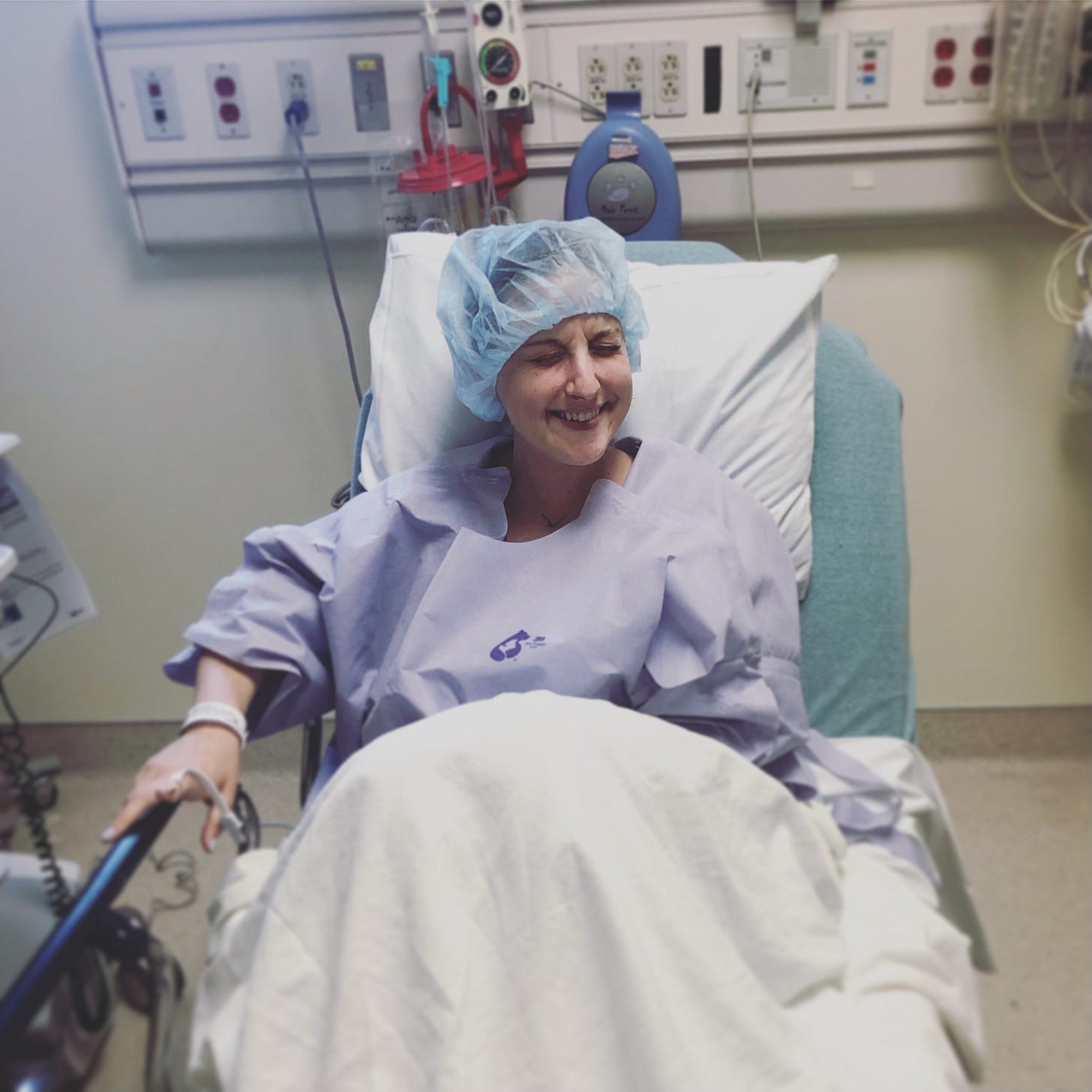

Reflecting on the anniversary of my bilateral mastectomy at age 29

Summertime five years ago, I lost my breasts.

It’s not like I misplaced them. I didn’t put them down somewhere and forget where they were, never returning to collect them.

No, it was much more violent than that. I was only twenty-nine, and yet, somehow, my right breast had become confused, containing cells which were growing out of control, cells that might hitch a ride elsewhere in my body, to places not so easily sliced off with a scalpel.

I went to sleep for six hours, not knowing what I’d look like when I woke up. I didn’t know how I would feel or not feel; the nerves in my chest cut through like strands of nuisance spider webs.

My tumour had been in a fortuitous location, earning me the right to keep my nipples, the incisions hidden beneath the creases of my breasts. So, when I first stripped off my bandages and took in my reflection, I still looked like me on the outside, as if the surgeon had only rearranged the furniture inside me. Sure, there was bruising and swelling, four tubes draining fluid from me, but it was a long way from the image of an outdated mastectomy.

When I attempt to count up my additional reconstruction surgeries, I arrive at four or five, though at a certain point, they merge in my mind, and I can’t discern one memory from another. There was the initial bilateral amputation with the placement of expanders. Then, the exchange of expanders for implants. There was a revision of my scars to help tighten rippling skin, plus a little fat grafting. After that, it gets murky. Did I have another one or two fat grafting sessions?

Despite the multiple surgeries, I’ve struggled with feeling highly critical of my reconstructed breasts. I used to stare at them before getting in the shower, noticing the divots where fat grafting never held or the way the implants seemed to burst forth rather than slope down from my chest.

Eventually, I decided that my hyper-awareness of my breasts was probably a bigger issue than the imperfections I perceived in them. And though I know I’ve been very lucky with my reconstruction outcome, the whole experience has felt like an alienation of self.

My nipples still harden from the cold; I just don’t feel it anymore. They are numb. Nipples without a purpose. They cannot feed an infant. They cannot bring me pleasure. They simply exist for the sake of it, which I know is something to be grateful for.

Only after the fact did I learn that reconstructed breast implants are held in place beneath the skin by a sort of sewn-in internal bra, the material used derived from cadaver tissue. Why no one thought this would be of interest to me prior, I can’t say. But now I have this image in my head of my breasts being held in place by a ghost. In my mind, this ghost is not malevolent, but he—yes, for some reason, my ghost is a man—is always present, even at times when he’s decidedly not invited.

When I look in the mirror now, I feel a curious sense of detachment, like I’m looking at the work of my surgeon and not my own body.

On some days, I think my boobs look pretty good. Good enough to photograph and send to newly diagnosed women awaiting mastectomies of their own.

On other days, my breasts are a reminder of the worst thing that ever happened to me. An omen of the ever-looming prospect of recurrence, low though it mercifully is.

On my worst days, my breasts are simply a reminder that I’m going to die one day, whether or not it’s from cancer, scarcely being the point.

And so it is that my breasts, organs which were once inextricably linked with life, have become intertwined with death.

I don’t feel sad about this—though maybe I should. My experiences with grief have taught me that quiet curiosity is sometimes the best thing to offer oneself. I have hope I won’t always feel this way.

I’ve come to realise that reconstructing my breasts cannot heal my loss. These very intimate parts of my body have been medicalised, but even before that, they harboured a tumour, the possibility of another loss, the loss of my life.

It’s been long enough now that I’m starting to forget what my natural breasts looked like. I only had them for fifteen years of my life.

I’m planning on living long enough that, eventually, these new ones will outlast the originals.

This writing is amazing. Glad to have found this Substack (by you finding mine, haha).

It's incredible how you can write about something so difficult, yet have a real vibrancy and humour to what you write!